Building the Beloved Community

By Rev. Anne Swallow Gillis — The beginning of Jesus’ public ministry is remarkable for what he does NOT say. One might expect him to jump right in with “Hello everybody, now I want you to love one another!” Or perhaps an admonition to act decent, caring, kind; something manageable on a person-to-person level. Why doesn’t he start there? Some days it seems to me that contemporary Christianity as we know it gets reduced to a warm fuzzy version of the love part. Or, maybe more to a small tangent of loving, which is polite, which is calming and not offensive, which is nice. But Jesus doesn’t start with talking about love. As much as we may say it is all about loving one another, Jesus does not begin with this interpersonal message. Instead, he goes bigger: He speaks of life in the public square. He goes right to the root of what “public” means: how we order our lives together as a group, how we govern ourselves because of who governs us. In a time when politics has sharply divided us as a nation, we so want the Jesus story to NOT be about politics.

But the Gospel of Matthew wants his readers to know that Jesus’ public ministry begins after he hears of a public and politically motivated act against John the Baptist. Jesus learns that John, his cousin and most likely his spiritual mentor, has been arrested and jailed by the local political ruler King Herod. Jesus leaves his home town and heads to Capernaum on the Sea of Galilee. And, from that time on, writes the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus begins proclaiming “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.” Jesus starts with a message about…politics! About governance, who is in charge and about how choices are made in this public realm. He says that the kingdom that rules the heavens, the reign of God, has come near. Not words that King Herod, nor the Roman Empire, would want to hear. The first public words out of his mouth are a radical political proclamation about our life together as a body, polis, community. And these words will eventually pit him against the political powers of the day and get him arrested and jailed and crucified. To simply spiritualize these words may put us at a safe distance. We can speak in generalities about God’s merciful love coming near and making everyone friendly and happy. But we will gain little insight into how in the world we navigate this time in our nation’s history as both citizens and Christians.

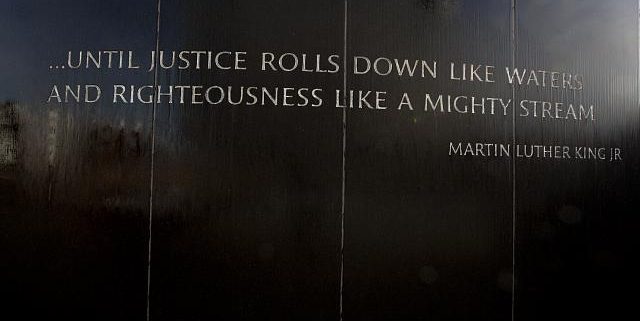

We are on the edge of a communally fraught week for our nation: on Monday, we celebrate a national holiday acknowledging the ground-breaking ministry and political proclaiming of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We do so in an era when racial inequity around housing, jobs, rates of imprisonment and health care, and resulting racial tension, continue to soar. Dr. King coined the phrase “the beloved community.” He spent his public life addressing the interwoven realities of racism, militarism and poverty, which he claimed conspired together to keep our nation from being such a community. All this, at the height of the Vietnam War. On Friday, we will witness the inauguration of a president whose election continues to cause deep, angry and chaotic divisions in our country. This is the reality, the context, into which this Matthew passage drops today.

The passage also lands in our Epiphany time, the season after Christmas when the light of Christ becomes an “epiphany,” a “manifestation” to the world. For the moment, whoever we may have voted for, it just doesn’t seem like there is much light. I resonated with Walter Bruggeman’s words this week. He is a retired Hebrew Bible scholar, author of over 70 books, and minister in the United Church of Christ. Here is the first part of his poem called: “Epiphany.”

On Epiphany day,

we are still the people walking.

We are still people in the dark,

and the darkness looms large around us,

beset as we are by fear,

anxiety,

brutality,

violence,

loss —

a dozen alienations that we cannot manage.

I would say, as a nation and as communities, we still are “people in the dark,” with much darkness looming “large around us.” With “a dozen alienations that we cannot manage.” In the midst of all this, we encounter Jesus again, who keeps saying heaven is coming near. And then he does this very odd thing of going up to a couple of fishermen and saying, “Follow me; I will make you fishers of people,” and the guys drop everything, I mean everything, and follow him. Leaving nets and catch and boats and family? Not a prudent move, it would appear. What are we to know here, those of us who feel like we are walking in the dark at the moment?

Jesus begins to proclaim, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near, is at hand.” Actually, this is the same thing John the Baptist has been saying. It’s a call for a change of heart, a change of behavior. Why? Because something has been tripped into motion. The kingdom of heaven is on the move, so to speak. The Greek word for kingdom is “basileia” and is translated in a number of different ways. Which means that Biblical scholars argue a lot about what this means: kingdom, rule, reign, empire. Throughout Hebrew scriptures, Jews spoke of God the king as creator and savior and judge, and that God’s kingdom/empire is already fully functional in heaven/the unseen realm. Jews were constantly getting in trouble with the prevailing authorities, the current occupying powers, because of this sense of covenant with, allegiance to, God’s empire.

The New Testament scholar Warren Carter has written how in first century usage, the word “basileia” also referred “to empires like Rome’s that assert rule over people and land. The Gospel’s use of the same term illustrates a common practice among colonized peoples.” He notes that people often cope with “imperializing power by using native traditions to redefine its language to produce a similar yet different meaning.” I see this as a sly and ultimately subversive approach, often used by the seemingly powerless or marginalized. We’re going to take back that word, “basileia,” empire, and apply it to God’s empire coming among us! We see this in the LGBTQ community: We’re going to take back that word “queer” and apply it to ourselves with pride! In the Matthew passage, Carter continues, the “writer imitates imperial language and structures (God’s dominating power) yet redefines them as the subsequent scene of Jesus’ healing and liberating power displays.”

Jesus, the unknown carpenter’s son from Nazareth, wanders in on the public scene and starts to indirectly talk politics. One might say, Jesus is referring to regime change. God’s kingdom, reign of justice, mercy and peace is happening here. Now. The “beloved community” God intends is at hand, it draws near. Jesus is going to start acting like his very presence, his teaching, his healing work, extends this regime change and reveals it. And who does he invite to join him first? Fishermen. Not the local bakers, artisans or tax collectors. All three gospels, Matthew, Luke and Mark, tell us his first students, followers, are fishermen. This is significant because the fishing industry of the time was more fully embedded in the imperial Roman economy that just about anything else. Warren Carter describes how “Rome asserted control over the land and sea, their production, and the transportation and marketing of their yields with contracts and taxes.” Boats, nets, your catch, where you pulled up your boat, who you sold to, prices, all regulated by the empire who also takes a huge cut. Professor Carter continues: “Jesus disrupts these men’s lives, calls them to a different loyalty and way of life, creates a new community, and gives them a new mission (fish for people). His summons exhibits God’s empire at work, this light shining in the darkness of Roman-ruled Galilee.” Come, follow me, and I will make you fishers of people. Now we move to the relational, the building of this beloved community. It’s going to be about how we live together, govern ourselves under God’s rule.

Carter also notes that Jesus will go on and heal people who have actually been physically damaged by living in the inequities of the Roman imperial system. At least 70 to 90 percent of the inhabitants of the region were living in poverty. Food insecurity, unclean drinking water, social stress, poor nutrition, frequent imprisonment and hard physical labor just to survive. Many of the illnesses that Jesus will cure are caused by these kinds of unjust conditions: body weakness and paralysis, blindness, mental instability, fevers. Professor Carter bluntly puts it this way: Jesus comes and starts to “repair imperial damage.” Jesus “enacts God’s life-giving empire.” When I read this, all of a sudden the healing stories of Jesus seemed more radical, more seditious, than I ever imagined. I also realized how closely these conditions of first century people’s lives parallels that of people of color in this nation today.

Martin Luther King Jr. called our nation to repair “imperial damage” of centuries of racism, militarism and poverty. And it was very hard for much of our nation to hear him. And the damage continues. How will we be about “damage repair” in the next four years? Let’s keep talking and praying about this. The rest of Walter Bruggeman’s poem is a starting point, as we begin this significant week:

We are — we could be — people of your light.

So we pray for the light of your glorious presence

as we wait for your appearing;

we pray for the light of your wondrous grace

as we exhaust our coping capacity;

we pray for your gift of newness that

will override our weariness;

we pray that we may see and know and hear and trust in your good rule.

That we may have energy, courage, and freedom to enact

your rule through the demands of this day.

We submit our day to you and to your rule, with deep joy and high hope.

And so may it be. Amen.